Polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) remain one of the most persistent toxic legacies in global electrical infrastructure. Despite a production ban effective in most countries since the late 1970s, an estimated 10 million tonnes of PCB-containing materials remain in the environment, with power transformers representing the dominant reservoir. The Stockholm Convention’s dual deadline — phase-out of in-service equipment by 2025 and environmentally sound management by 2028 — is creating an unprecedented compliance wave that the vast majority of nations are ill-equipped to address. This article examines the current state of the problem through the lens of international regulatory frameworks, particularly the UN/UNEP guidelines and their operationalization in the EU and Italy, discusses the challenges of mass inventory campaigns, and proposes a data-driven alternative: the exploitation of pre-existing transformer inventory data and operational parameters to probabilistically identify PCB contamination risk without exhaustive laboratory testing. Early work in this direction suggests that specific age, manufacturer, geographic, and operational patterns encode statistically significant information about the likelihood and level of contamination — opening a path to intelligent, risk-stratified sampling that could dramatically reduce the cost and time of global compliance programmes.

1. The chemistry and toxicology of PCBs in electrical insulating fluids

Polychlorinated biphenyls constitute a family of 209 synthetic organic congeners derived from the biphenyl backbone through chlorine substitution at 1 to 10 positions. Industrially they were produced as complex multi-congener mixtures — principally under the trade names Aroclor (USA, Monsanto), Askarel (generic), Pyranol, Clophen, Kanechlor, Sovol, and Phenoclor — with total global production estimated at approximately 1.33 million metric tonnes between 1929 and 1993 (Breivik et al., 1999; PCB Elimination Network, UNEP). In the context of electrical equipment, PCBs were valued for a combination of properties that mineral oil alone could not offer: exceptional thermal stability, high dielectric constant, non-flammability, and chemical inertness. These same properties that made them industrially desirable are precisely what make them environmentally catastrophic.

The persistence of PCBs in the environment is a direct function of their degree of chlorination. Lightly chlorinated congeners (mono- to di-chlorobiphenyls) have environmental half-lives measured in weeks; heavier congeners such as hexa- to deca-chlorobiphenyls persist for decades to centuries. This differential degradation rate is why the congener profile of aged transformer oil differs markedly from the original commercial formulation — a fact with direct analytical and regulatory implications, as discussed in Section 3. The octanol–water partition coefficient (log Kow) of typical PCB congeners ranges from 4.5 to over 8, conferring extreme bioaccumulability. PCBs magnify through trophic levels, achieving concentrations in apex predators — including humans — that are several orders of magnitude above environmental background. Studies in populations with high dietary exposure have documented immune system suppression, thyroid disruption, hepatotoxicity, neurodevelopmental impairment in children exposed in utero, and elevated cancer risk, particularly non-Hodgkin lymphoma and hepatocellular carcinoma (WHO IARC Group 1 carcinogen classification, 2016).

2. The scale of the problem: global inventory and the 2028 challenge

2.1 The global stockpile

The UNEP Secretariat’s 2016 consolidated assessment placed total global PCB stocks at approximately 17.4 million tonnes of PCB-containing materials at peak production, of which only 3 million tonnes (17%) had been eliminated by that date — at an elimination rate of approximately 200,000 tonnes per year since 2000. To reach the 2028 target, the elimination of 1 million tonnes of PCB-containing oils and contaminated equipment per year would be required — a five-fold increase over the observed rate. The updated assessment by Melymuk et al. (2022, Environmental Science & Technology) provides a more sobering picture: over 10 million tonnes of PCB-containing materials remain globally, with at most 30% of countries currently on track to achieve environmentally sound management by 2028.

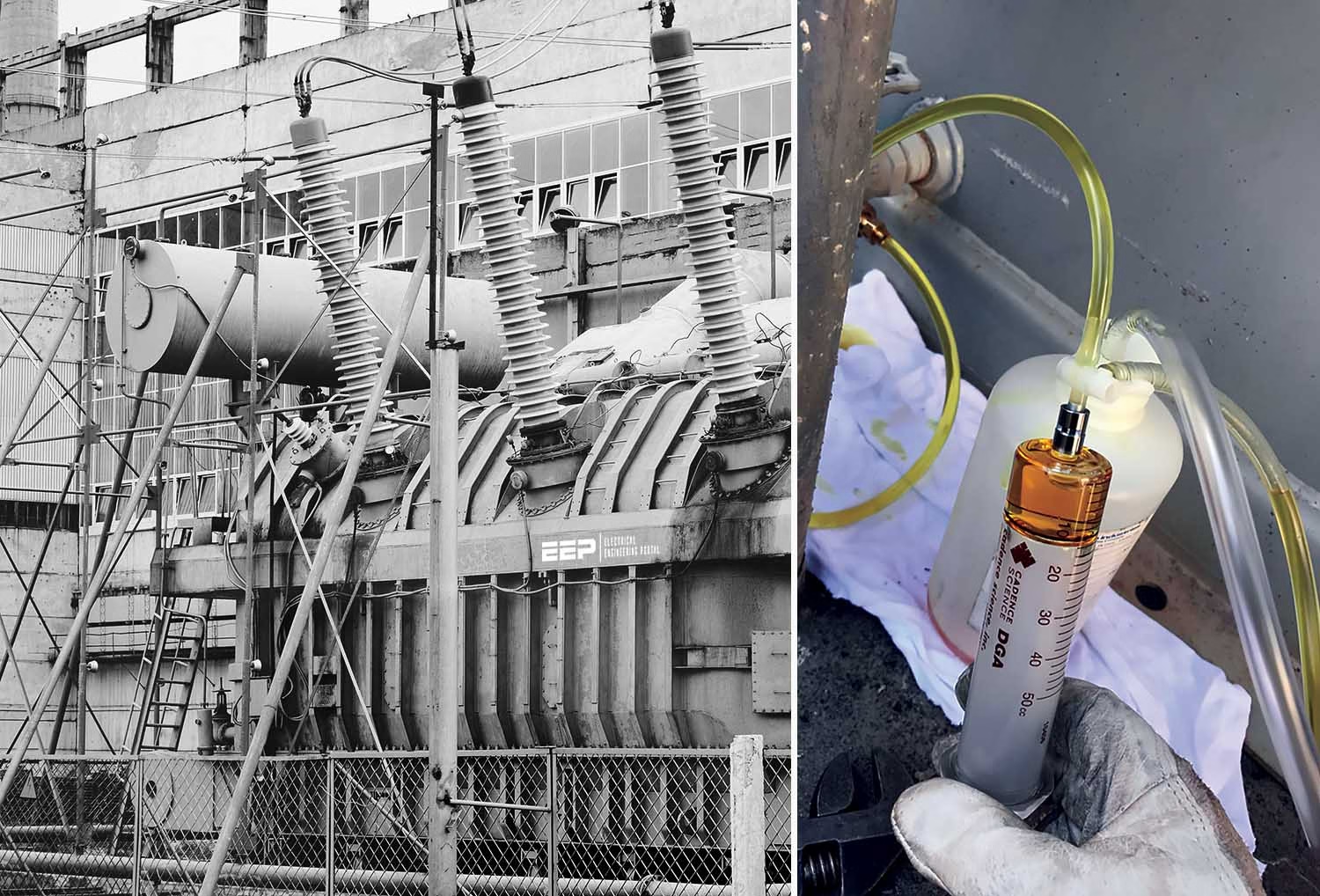

Power transformers account for the largest fraction of this stockpile by mass. Capacitors, fluorescent light ballasts, heat transfer equipment, and hydraulic systems constitute secondary reservoirs. In the energy sector specifically, the contamination problem is compounded by the phenomenon of cross-contamination: PCB-free transformers serviced with contaminated oils, shared maintenance equipment, or incompletely decontaminated oil regeneration systems acquire PCB loadings that, while below the strict 50 ppm threshold, may accumulate over time and over successive maintenance cycles. One of the main holders of PCB equipment is the energy production and distribution sector, where accidental cross-contamination of PCB-free transformers is prone to lead to further PCB contamination.

2.2 Differential progress across nations

The contrast between compliant and non-compliant nations reveals a structural inequality that international policy has struggled to address. Canada (Ontario) and the Czech Republic have achieved near-complete elimination of their PCB stocks, having reduced pure PCB inventories by 99% in a decade. The United States, notably a non-party to the Stockholm Convention, presents a paradox: despite having the world’s largest historical PCB production and use, regulatory compliance has been historically managed under the TSCA (Toxic Substances Control Act) framework independently of the global treaty. In 2006, the USA had 14,457 transformers containing 47,500 tonnes of PCB material and 770 tonnes of pure PCBs, with only approximately 3% decrease in pure PCBs since 2006.

The most critical gaps lie in sub-Saharan Africa, South and Southeast Asia, and parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia, where the combination of aging legacy infrastructure installed before 1977 bans, limited analytical laboratory capacity, inadequate regulatory frameworks, and scarce financial resources creates a near-perfect storm of non-compliance. Countries in these regions often face the additional challenge that their grids were partly supplied with second-hand equipment, including transformers, from industrialized nations — equipment that may carry PCB contamination as an invisible inheritance.

3. International regulatory framework: the UN/UNEP Guidelines in depth

3.1 The Stockholm convention: architecture and obligations

The Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants, adopted in 2001 and entering into force in May 2004, constitutes the central international instrument governing PCBs. To date, 181 countries around the world have become Parties to the Stockholm Convention. PCBs are listed under Annex A (Elimination) of the Convention, which prohibits new production and use while imposing specific obligations for existing stocks.

Part II of Annex A establishes the binding operational timeline that is currently defining global compliance pressure:

- By 2025: Eliminate the use of PCBs in equipment containing greater than 50 ppm

- By 2028: Environmentally sound waste management of liquids containing PCB and equipment contaminated with PCB having a PCB content above 0.005% (50 mg/kg), as soon as possible but no later than 2028

The threshold of 50 ppm (equivalent to 50 mg/kg or 0.005% by weight) represents the definitional boundary between “PCB equipment” subject to mandatory elimination and equipment deemed PCB-contaminated at sub-regulatory levels. The Convention’s text recognizes two distinct categories: equipment manufactured as PCB-containing (e.g., original Askarel-filled transformers) and equipment inadvertently contaminated through maintenance practices.

3.2 UNEP guidance documents: a technical roadmap

The UNEP has published a series of technical guidance documents that operationalize the Stockholm Convention’s obligations into actionable frameworks. The most relevant for transformer asset managers include:

UNEP/POPS/COP.10/INF/12/Rev.1 — “Draft Guidance for Development of PCB Inventories and Analysis of PCB” (2022): This document, updated from earlier versions and presented to the 11th Conference of the Parties (COP.11, 2023), provides standardized methodologies for national inventory construction. It addresses sampling strategies, analytical methods (with GC-ECD per IEC 61619 as the reference technique), quality assurance protocols, and data management. Critically, it acknowledges the problem of incomplete national reporting — at the time of the February 2019 progress report, only 59 of 182 Parties had submitted their fourth national report, illustrating the governance gap between treaty obligations and practical implementation.

“PCBs in the Stockholm Convention — Draft Guidance for Development of PCB Inventories” (UNEP/POPS/COP.11/INF/12, 2023): The COP.11 iteration refines earlier guidance with updated concentration thresholds, improved tiered sampling methodologies, and considerations for handling the congener profile complexity of aged oil.

Basel Convention Technical Guidelines — “Environmentally Sound Management of Wastes Consisting of, Containing or Contaminated with PCBs, PCTs or PBBs” (Updated 2023): The Basel Convention provides the parallel framework governing transboundary movement and disposal of PCB-contaminated waste. The 2023 update to these technical guidelines aligns with Stockholm Convention requirements and specifies destruction efficiency requirements for thermal treatment: >99.9999% for liquids, >99.9998% for gases — the “six nines” standard required to prevent dioxin and furan formation during incineration.

UNEP PCB Phase-out Plan (2023): This document, produced in the framework of the GEF Project on Southern Africa PCB disposal, provides a model for national-level phase-out planning and contains the cost-effectiveness model developed by UNEP for evaluating the economic benefits of PCB elimination and infrastructure upgrading.

MapX Platform for PCB Spatial Management (UNEP, ongoing): UNEP’s work with the MapX geographic data platform represents an important innovation in inventory management, enabling countries to geospatially visualize and manage their PCB equipment registries. This data infrastructure is relevant context for the AI-driven approaches discussed in Section 5.

3.3 European Union: regulation 2019/1021 and national implementations

The European Union’s framework for PCBs is anchored in Regulation (EU) 2019/1021 (the revised POPs Regulation, recast from EC 850/2004), which implements Stockholm Convention obligations with specific EU adaptations. UK Government Guidance, aligned with the Stockholm Convention, states: “Member states shall identify and remove from use equipment containing more than 0.005% PCBs and volumes greater than 0.5dm³, as soon as possible but no later than 31st December 2025.” The UK, post-Brexit, has maintained equivalent obligations through its own legislation (UK RPS 246, Environmental Permitting Regulations 2010 as amended).

Italy’s implementation is governed by D.Lgs. 209/1999 (implementing the earlier EU Directive 96/59/EC on PCB/PCT disposal), as clarified by a MASE (Ministero dell’Ambiente e della Sicurezza Energetica) interpretive ruling published in August 2025 in response to a Confindustria query. The MASE ruling confirmed that EU Regulation 2019/1021 prevails over the earlier national decree, and that transformers with PCB concentrations between 50 and 500 mg/kg (the “contaminated” category) are subject to the same December 2025 decommissioning requirement as outright PCB equipment. Operators must maintain inventories and registration records, with decontamination or disposal through certified operators as the only compliant pathway.

3.4 United States: TSCA and EPA framework

The USA’s regulatory framework under TSCA (15 U.S.C. § 2605) predates the Stockholm Convention and operates independently of it. The EPA’s PCB regulations (40 CFR Part 761) have prohibited the manufacture of PCBs since 1979 and the use of PCB transformers (>500 ppm) in or near commercial buildings since 1990. Key elements include mandatory registration of PCB transformers exceeding 499 ppm, annual performance inspections, spill containment requirements, and mandated high-temperature incineration (>1200°C, >2 seconds residence time) as the primary approved disposal method. While EPA data suggests significant progress in the large-utility segment, the non-residential transformer population below the 500 ppm threshold remains poorly characterized.

4. Analytical methods and inventory challenges

4.1 Reference analytical methods

The standard analytical method for PCB determination in transformer oil is gas chromatography with electron capture detection (GC-ECD), referenced in IEC 61619:2022 (“Insulating liquids — Contamination by polychlorinated biphenyls — Method of determination by capillary gas chromatography”). The technique quantifies the sum of representative indicator congeners (typically a defined multi-congener panel including CBs 28, 52, 101, 138, 153, 180, and others, calibrated against commercial Aroclor standards) and extrapolates total PCB concentration. The method has a detection limit in the range of 1–5 ppm under optimized conditions, comfortably below the 50 ppm action threshold.

For field screening, immunoassay-based rapid test kits have been validated for qualitative or semi-quantitative determination, enabling preliminary assessment before laboratory confirmation. However, these methods are subject to matrix interferences from mineral oil and may give false positives or negatives with certain Aroclor profiles, particularly in aged oil where weathered congener distributions differ significantly from the calibration standards.

4.2 The inventory problem: scope, cost and incompleteness

A national-scale transformer PCB inventory involves systematic sampling of in-service transformers, decommissioned transformers in storage, and ancillary fluid stocks. The UNEP Inventory Guidance identifies four categories of information that must be captured: equipment containing PCBs in operation, decommissioned equipment stored for disposal, contaminated liquids, and other contaminated materials. The completeness of these inventories is the Achilles’ heel of global PCB management.

National reporting to the Stockholm Convention Secretariat reveals systematic gaps. Difficulties in estimating quantitative PCB data arise from incomplete national reporting, limited coverage of voluntary survey responses, incomplete and inconsistent inventories — with countries reporting differently on equipment in operation, decommissioned equipment, and contaminated liquids — lack of analytical methods to identify PCB waste, and diverse interpretation of “PCBs in use.”

A full analytical inventory of all in-service mineral-oil-filled transformers in a medium-sized country requires laboratory analysis of thousands to tens of thousands of samples. At a typical analytical cost of €150–500 per sample (depending on method, throughput, and country), the total cost of a comprehensive national inventory can reach tens of millions of euros — a prohibitive sum for many developing nations. Field sampling logistics add further costs: transformer oil sampling requires safety procedures, confined-space protocols in substation environments, and documentation chains that multiply per-unit costs. The result is that most countries have conducted partial inventories, prioritizing high-voltage transmission assets and leaving medium-voltage distribution transformers — which represent the large majority of the installed base by unit count — incompletely characterized.

5. Beyond mass sampling: an AI-assisted approach to PCB risk stratification

5.1 The scientific basis: PCBs as a temporally-encoded signal

A key insight that opens the door to intelligent inventory approaches is the following: while PCBs do not degrade in transformer oil under normal operating conditions, their presence is not random. The contamination landscape of a transformer fleet is, in fact, highly structured by manufacturing history, installation date, maintenance practices, geographic procurement patterns, and oil service history. Several independent lines of evidence support this:

Manufacturing-period effect: The use of PCBs as dielectric fluids was concentrated in the period between approximately 1940 and 1977, with the peak occurring in the 1960s. Transformers manufactured after 1985 in most industrialized countries can be assumed PCB-free with high probability. The probability of contamination is therefore a strong function of manufacturing year, following a distribution that mirrors industrial PCB use patterns by country and sector.

Manufacturer and country-of-origin effects: Some manufacturers used PCBs systematically in certain product lines and voltage classes; others did not. Regional procurement patterns created geographic clustering of contamination. An Iranian national grid study found that statistical analysis indicated that the year of manufacture and manufacturing company provided significant effects on PCB contamination (p value <0.001), with 0.5% of transformer oils exhibiting levels above 50 ppm, but highly concentrated: the contaminated oils contained 91.4% of all detected PCBs despite representing only 1.9% of transformers analyzed. This extreme skewness — a handful of highly contaminated assets accounting for the vast majority of total PCB mass — is consistent with a structured, predictable contamination pattern rather than a stochastic one.

Cross-contamination traceability: In grids where maintenance records are available, oil service history (oil top-up events, oil filtration, oil reclamation) can be used to trace contamination propagation through a fleet. Maintenance equipment shared between PCB and non-PCB transformers is a known amplification mechanism.

Oil chemistry as a proxy indicator: Standard transformer oil tests — particularly acidity, interfacial tension, dielectric strength, and dissolved gas profiles — encode information about oil history and service conditions that may correlate with PCB risk. The aging products of mineral oil and synthetic esters differ chemically from those of PCB-based fluids, and residual chemical signatures may persist even after oil substitution.

5.2 Towards a rpedictive PCB risk model

The working hypothesis currently under investigation at Seetalabs is that existing transformer inventory data — the kind routinely collected for asset management purposes, including nameplate data, installation and maintenance records, and historical DGA and oil quality parameters — contains sufficient statistical information to generate a PCB contamination risk score for individual assets. This risk score would not replace laboratory confirmation, but would enable risk-stratified sampling: testing the 10–15% of the fleet at highest predicted risk first, where probabilistic models suggest that 70–80% of contaminated units will be concentrated.

The approach draws directly on the feature engineering methodology developed for RONIN AI’s transformer health indexing system. Just as the THI model learned to predict overall condition from a compact set of 14 indicators, a PCB risk model would learn to assign contamination probability from a feature set drawn from:

- Nameplate features: manufacturing year, rated voltage, rated power, manufacturer, cooling class, country of manufacture

- Installation context: geographic region, customer sector (industrial, utility, commercial), installation date, operational history

- Oil service history: number of oil top-up events, oil filtration records, oil reclamation records, oil origin and supplier

- Historical oil chemistry parameters: trends in acidity, IFT, BDV, moisture, tan delta, and DGA gases — particularly looking for patterns atypical for age and service conditions

- Maintenance event history: inspection records, previous non-routine interventions

The challenge, and the reason this work remains active research rather than a deployed product, lies in constructing a labelled training dataset of sufficient size and representativeness. Unlike the THI model, where ground-truth health index labels can be derived algorithmically from established CIGRE methodology, the PCB risk model requires confirmed laboratory PCB measurements as ground-truth labels — and these measurements are precisely the data that is sparse and inconsistently collected. Strategies being explored include federated learning approaches that aggregate partial inventory data across multiple utilities, transfer learning from the substantial body of historical PCB survey data embedded in regulatory submissions, and active learning frameworks that direct sampling towards the most informationally valuable assets.

5.3 Feature importance hypotheses

Based on domain knowledge and available literature, the following features are hypothesized to have high predictive importance in a PCB risk model:

Manufacturing year (most important): The probability of PCB use follows a strong temporal pattern aligned with industrial production history. A transformer manufactured in 1965 carries far higher a priori PCB risk than one manufactured in 1990.

Manufacturer identity: Documented through institutional memory, industry databases, and regulatory submissions for major utilities. Manufacturers known to have used Askarel formulations in specific product lines would contribute a positive risk signal.

Voltage class: High-voltage (100+ kV) transmission transformers were preferentially filled with PCB-based fluids due to fire safety regulations in indoor substations; distribution-class units (10–35 kV) show more variable patterns.

Oil acidity trend pattern: The acidification rate of PCB-containing oil under thermal stress differs from mineral oil — a potential indirect discriminant.

IFT trajectory: Interfacial tension degradation kinetics in PCB blends may differ from pure mineral oil, providing a long-term observable signal.

Anomalous DGA patterns: Specific constellations of dissolved gases that are inconsistent with the transformer’s thermal and electrical history may indicate the presence of a non-standard fluid.

5.4 The cross-contamination pattern problem

One of the most technically interesting aspects of PCB contamination in working transformer fleets is the phenomenon of cross-contamination propagation. In power grids where centralized oil maintenance practices were historically applied — using shared filtration trucks, common oil storage, or standardized top-up procedures across a mixed fleet — PCB contamination can propagate through an initially clean fleet over time. This propagation follows network topology: substations sharing maintenance crews or oil supplies form contamination clusters. Network graph analysis of maintenance event records could theoretically identify these clusters and predict propagation risk even in the absence of direct PCB measurements on all nodes.

This is an area where the spatial data capabilities being developed under UNEP’s MapX platform for national inventories could be combined with machine learning graph models to map contamination networks — a conceptually ambitious but technically tractable research direction.

6. Disposal technologies and the end-of-life challenge

6.1 Approved treatment technologies

The Stockholm and Basel Conventions require that PCB-containing waste be treated using methods achieving a destruction and irreversible transformation (DIT) level that effectively eliminates the PCB hazard. The approved methods include:

High-temperature incineration (HTI): The primary and most widely accepted method. Requires combustion at >1,200°C with >2 seconds residence time, followed by acid gas scrubbing to prevent HCl and dioxin/furan formation. Applicable to oils, solids, and contaminated equipment after dismantling.

Chemical dechlorination: Processes including sodium-metal reduction, polyethylene glycol-based systems (KPEG, APEG), and base-catalyzed decomposition (BCD) that break the carbon-chlorine bonds chemically under controlled conditions. Applicable primarily to PCB liquids; produces chloride salts and hydroxylated biphenyls requiring further treatment.

Plasma-arc incineration: High-energy plasma processes achieving very high temperatures (>10,000°C in the plasma zone); effective for recalcitrant organic contaminants but capital-intensive and primarily available in industrialized countries.

Ball milling with chemical reagents (mechanochemical treatment): An emerging technology that achieves PCB dechlorination through grinding with calcium oxide or similar reagents. Lower energy requirements and suitability for decentralized operations make this attractive for developing nations, where certified HTI facilities may not exist within economic transport distance.

6.2 The economic case for elimination

UNEP’s cost-effectiveness model for PCB phase-out includes quantification of indirect economic benefits that often substantially exceed direct disposal costs. For a fleet of aging PCB transformers, the relevant benefits include: avoided incident costs from PCB-related fire or spill events (remediation, liability, business interruption); energy loss reduction from replacing inefficient legacy units; avoided health costs from reduced PCB environmental burden; and carbon footprint reduction from more efficient modern transformers. UNEP developed a Model (spreadsheet) to evaluate and quantify the economic benefits of PCB removal and infrastructure upgrading, calculating the cost-effectiveness payback period and estimating the necessary investment and the benefits.

7. The 2025 Deadline: state of compliance and outlook

7.1 EU: near-completion in compliant states

Within the European Union, the 2025 deadline has catalyzed significant compliance activity over the 2020–2025 period. A 2022 EU audit found that 95% of legacy PCB transformers had been decommissioned in compliant member states. Italy, Germany, France, and the Nordic countries have largely completed their PCB transformer phase-out for the utility sector, with residual challenges concentrated in the industrial sector (large industrial customers with aging on-site substations) and in the medium-voltage distribution network where legacy assets persist in smaller utilities and co-operatives.

The post-deadline regime — mandatory decontamination or disposal of all identified PCB equipment as soon as possible after December 31, 2025 — creates ongoing obligations that will extend into the 2026–2028 window. The MASE clarification for Italy confirmed that there are no extensions available under the current regulatory framework, maintaining pressure on industrial operators who may have deferred action.

7.2 Global picture: a structural shortfall

The global picture is far less optimistic. The 2019 COP.9 progress report highlights the difficulties in estimating quantitative PCB data, with only 59 Parties out of 182 having submitted their fourth national report by the deadline. Many developing nations lack the three prerequisites for effective PCB elimination: complete inventories, certified disposal capacity within national borders, and financing mechanisms for replacement infrastructure. In developing countries, some transformers produced before 1990 that may contain hazardous levels of PCBs in the cooling fluid are still in use, presenting health risks to humans and the environment and involving high energy losses.

The UNDP and UNEP are active in this space through the Global Environment Facility (GEF), supporting national inventory projects and disposal campaigns in priority countries. The Southern Africa Power Pool (SAPP) regional project has developed model training materials and coordinated technical workshops across the SADC region. But the scale of the remaining problem dwarfs current programme capacity.

8. Intersections with transformer health indexing

The problem of PCB contamination in transformer oil is not separate from the broader challenge of transformer health assessment — it is deeply embedded within it. Several considerations connect the two domains:

PCBs and DGA interpretation: The presence of PCBs in transformer oil does not directly generate characteristic DGA gases, but PCB-containing fluids have different thermal degradation pathways that can produce atypical DGA patterns under fault conditions. The chlorine content of PCB molecules means that thermal decomposition produces hydrogen chloride (HCl) and chlorinated hydrocarbons alongside conventional DGA gases — signals that standard DGA interpretation methods are not designed to recognize. An AI-based health indexing model trained exclusively on non-PCB data may misclassify the condition of PCB-contaminated transformers.

Oil quality parameters as contamination proxies: The key physical-chemical parameters used in transformer health assessment — interfacial tension, acidity, dielectric breakdown voltage, tan delta, and moisture content — have different baseline values and aging trajectories in PCB-based and mixed PCB/mineral oil environments. A transformer health model that ignores PCB status risks systematic bias in its health predictions for contaminated assets.

Fleet-level risk clustering: The same asset registry data that supports transformer health fleet management — manufacturer, age, installation date, voltage class, maintenance history — constitutes the feature space for PCB risk modelling. Integration of PCB contamination probability as a meta-feature within health indexing systems is a natural and valuable extension. A RONIN AI-like system augmented with a PCB risk layer would provide asset managers with a more complete risk picture: not only “how healthy is this transformer?” but also “what is the probability that it contains a legacy contaminant that requires mandatory remediation?”

9. Conclusions and research directions

The 2025 Stockholm Convention deadline has brought the PCB transformer problem to a critical juncture. In compliant jurisdictions — primarily the EU and some other OECD nations — the end of in-service use is effectively complete for the large utility sector, but residual issues remain in the industrial and medium-voltage segments. Globally, the picture is one of systemic undercompliance, with the 2028 environmentally sound management deadline at serious risk of not being met by the majority of parties.

The central challenge going forward is not technological — the methods for identifying and disposing of PCB contamination are well understood — but informational and economic. We do not know with sufficient precision where the remaining contaminated equipment is, particularly in developing nations and in the lower voltage tiers of distribution grids in otherwise compliant countries. Mass sampling campaigns to close this gap face prohibitive costs and logistical complexity.

The most promising path forward combines three elements. First, the systematic consolidation and standardization of existing inventory data across utilities, national registries, and international databases — a process that the UNEP MapX platform is beginning to enable. Second, the application of machine learning methods to extract probabilistic risk scores from this consolidated data, enabling intelligent risk stratification that directs laboratory sampling where it has the highest expected information value. Third, the integration of PCB risk assessment into the broader framework of transformer asset management and health indexing — treating contamination risk as a dimension of overall asset risk that deserves the same data-driven, systematic treatment as thermal aging, insulation degradation, and electrical fault history.

The initial feature engineering work to identify the minimum set of inventory attributes that encode meaningful PCB contamination risk — analogous to the reduction from 63+ indicators to 14 features achieved in RONIN AI’s health index model — is currently underway. The underlying hypothesis is that a handful of temporal, geographic, and operational attributes, combined with oil chemistry signatures accessible through routine condition monitoring, could reduce the required sampling universe by 60–80% while recovering 85–90% of contaminated assets. If validated, this approach would transform what is currently an economically and logistically intractable problem into a tractable, prioritized remediation programme.

The legacy of PCBs will outlast the 2028 deadline. But the combination of improved data infrastructure, intelligent risk stratification, and integrated health management systems offers a credible path to closing the information gap that has allowed this legacy to persist for so long in our power infrastructure.

References and further reading

International Framework:

- Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (2001, entered into force 2004). Annex A, Part II — Polychlorinated biphenyls.

- UNEP. (2023). Polychlorinated Biphenyls Phase-out Plan. UNEP/GEF Project 5532, Southern Africa.

- UNEP. (2022). Draft Guidance for Development of PCB Inventories and Analysis of PCB. UNEP/POPS/COP.10/INF/12/Rev.1.

- UNEP. (2019). Report on progress towards the elimination of polychlorinated biphenyls. UNEP/POPS/COP.9/INF/10.

- UNEP/Basel Convention Secretariat. (2023). Technical Guidelines for the Environmentally Sound Management of Wastes Consisting of, Containing or Contaminated with PCBs. Updated edition.

EU and National Regulation:

- European Commission. Regulation (EU) 2019/1021 on persistent organic pollutants (recast). Official Journal of the European Union.

- MASE (Ministry of Environment and Energy Security, Italy). Interpello Confindustria, August 2025 — PCB Transformer Compliance Clarification.

- UK Environment Agency. Regulatory Position Statement RPS 246. Use and disposal of PCB-containing oil-filled electrical equipment.

Scientific Literature:

- Melymuk, L., Blumenthal, J., Sáňka, O., et al. (2022). Persistent Problem: Global Challenges to Managing PCBs. Environmental Science & Technology, 56(13), 9029–9040. DOI: 10.1021/acs.est.2c01204.

- Breivik, K., Sweetman, A., Pacyna, J.M., Jones, K.C. (1999). Towards a global historical emission inventory for selected PCB congeners — A mass balance approach. Science of the Total Environment, 290, 181–198.

- Shayegan, Z., et al. (2017). Transformer oils as a potential source of environmental exposure to polychlorinated biphenyls: an assessment in three central provinces of Iran. Environmental Science and Pollution Research, 24, 25014–25025. DOI: 10.1007/s11356-017-9576-2.

Standards and Technical Guidelines:

- IEC 61619:2022. Insulating liquids — Contamination by polychlorinated biphenyls — Method of determination by capillary gas chromatography.

- IEEE Std 62637. Guide for Acceptance of Mineral Insulating Oil from Serviced Electrical Equipment.

- CIGRE TB 761. Health Index for Power Transformers. WG A2.44.

AI and Transformer Health:

- Seetalabs. (2021). RONIN AI — Transformer Health Index Prediction: White Paper. Available at www.seetalabs.com.

- Chen, T., & Guestrin, C. (2016). XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 785–794.